Mimetic Theory and Investing

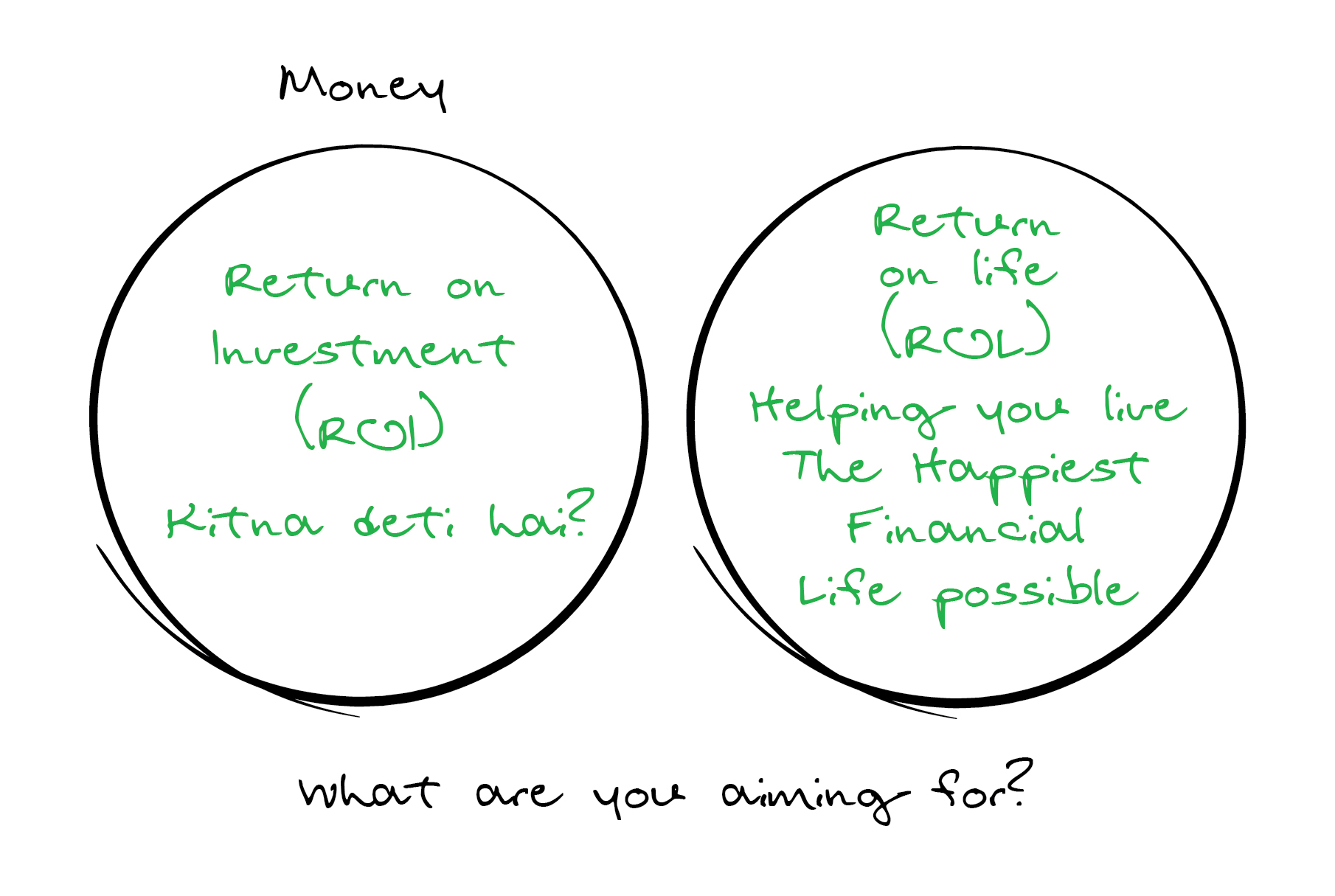

In my post “Happyness -The Only Goal that Matters”, I had referred to two words ‘Mimetic Desire’ and had promised to write on this. Well, it’s time to cover this key topic. Because unknown to most of us, mimetic desire affects every walk of our life including investing. Mimetic Desire in its simplest form means that we learn what to desire only by observing others.

In the book “Wanting”, Author Luke Burgis wonderfully covers this subject. It is a book about why people want what they want. In short, why you want what you want. Luke attributes the mimetic theory discovery to Rene Girard, a professor of literature and history. He writes, “Mimetic theory isn’t like learning some impersonal law of physics, which you can study from a distance. It means learning something new about your own past that explains how your identity has been shaped and why certain people and things have exerted more influence over you than others.”

It’s never easy to do this because we can never see ourselves. Thus, we always need a mirror to look at ourselves. While we can look at ourselves physically in a mirror, we all need many other mirrors- a professional mirror to help us figure what we want, an investing mirror to help us figure out what we want out of investing and several other mirrors (or models) for different areas of our lives. All of us hold so many assumptions that have turned into beliefs. The basic assumption we all carry is that our thinking is a function of our thinking.

Luke adds further, “An idea that challenges commonly held assumptions can feel threatening– and that’s all the more reason to look more closely at it: to understand why.

An unbelieved truth is often more dangerous than a lie. The lie in this case is the idea that I want things entirely on my own, uninfluenced by others, that I am the sovereign king of deciding what is wantable and what is not. The truth is that my desires are derivative, mediated by others, and that I am a part of an ecology of desire that is bigger than I can fully understand.”

Many (not all) sellers in the investment world (and outside) understand this very well.

Thus, they will make nonsensical statements such as:

- Rameshji has invested so much money of his own in this PMS/Fund.

- This bull has taken a large position in this stock.

- All these big investors and institutional investors have already invested in this round. You get to participate with them.

- Mutual Funds are for retail investors. You are special so we have this Private Equity Fund, PMS or AIFs.

- We know how to time the markets. Thus, I was (not) shocked to see a sales head from an asset management company recently remark – “You can, and you must time the market.”

Without knowing mimetic theory, they understand the power of desire.

Luke writes, “Girard discovered that we come to desire many things not through biological drives or pure reason, nor as a decree of our illusory and sovereign self, but through imitation.

Desire, as Girard used the word, does not mean the drive for food or sex or shelter or security. Those things are better called needs – they are hardwired into our bodies. Biological needs don’t rely on imitation. If I am dying of thirst in the desert, I don’t need anyone to show me that water is desirable.

But after meeting our basic needs as creatures, we enter into the human universe of desire. And knowing what to want is much harder than knowing what to need.”

“In the universe of desire, there is no clear hierarchy. People don’t choose objects of desire the way they choose to wear a coat in the winter. Instead of internal biological signals, we have a different kind of external signal that motivates these choices: models.

Models are people or things that show us what is worth wanting. It is models – not our objective analysis or central nervous system – that shape our desires. With these models, people engage in a secret and sophisticated form of imitation that Girard termed mimesis(mi-mee-sis), from the Greek word mimesthai (meaning to imitate).”

In the world of entrepreneurship, the models of desire are Elon Musk, Jeff Bezos, Steve Jobs and so on. In the world of investing, the models of desire are Warren Buffett, Charlie Munger, Peter Lynch, Cathie Wood (in recent times), and so on. Closer home, it is Rakesh Jhunjhunwala. There are many others whose names are taken generously by PMS providers and product manufacturers to sell products.

As humans have evolved, people have spent less time concerned about surviving and more time striving for things – less time in the world of needs and more time in the world of desire.

You may be wondering then: if desire is generated and shaped by models, then where do models get their desires? The answer – from other models.

Warren Buffett got his from Benjamin Graham. Rakesh Jhunjhunwala might have got it from Harshad Mehta.

Who are your models of desire in investing?

- Are they people who make you believe they can time the markets?

- Are they people who make you believe they can forecast the economy, and the stock markets?

- Are they people who make you believe that they can provide the highest (or high) returns?

I hope the answer to the above three questions is “None of the Above.”

and then tap on

and then tap on

0 Comments